Pas De Deuxby Kim Benson, Moyra Davey, Justine Di Fiore, David Goldes, Jay Heikes, Pao Houa Her, Alexa Horochowski, Ruben Nusz, JoAnn Verburg

Jun 26 – Aug 10, 2024

Justine Di Fiore, Undergrowth, 2024. Oil on Canvas (Diptych). 30 x 53½ in.

David Goldes. Under the Sheltering Sky, 2024. Graphite, molding paste, black gesso on paper. 27 x 22 in.

Ruben Nusz, After Morandi, 2019-2024

Distemper on linen. 8 x 10 in.

Ruben Nusz, After Morandi, 2019-2024

Distemper on linen. 8 x 10 in.

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (from the series My Mother’s Flowers), 2016

Archival pigment print, Edition of 3 + 1AP. 40 x 32 in.

Ruben Nusz, After Morandi, 2019-2024

Distemper on linen. 8 x 10 in.

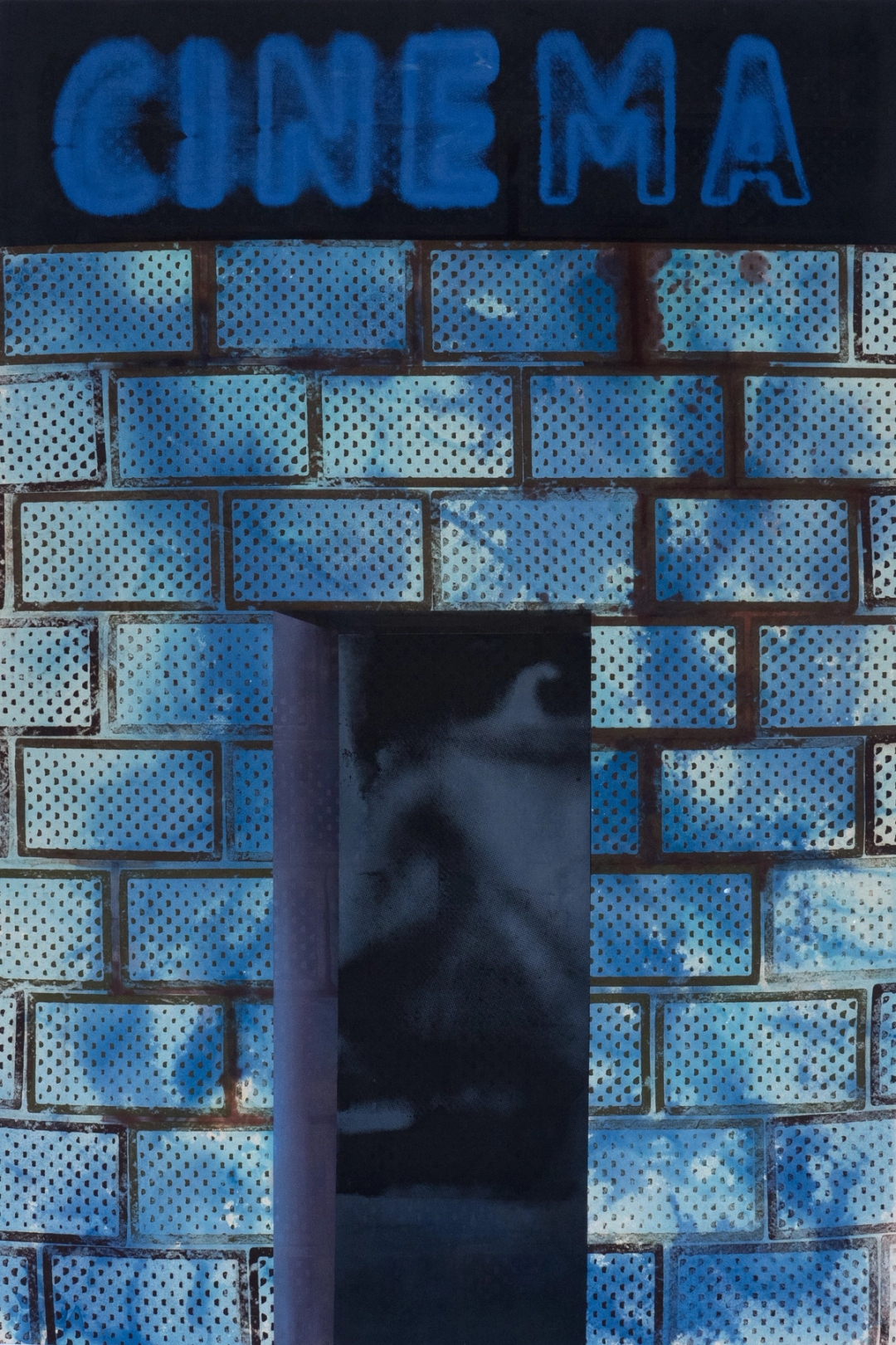

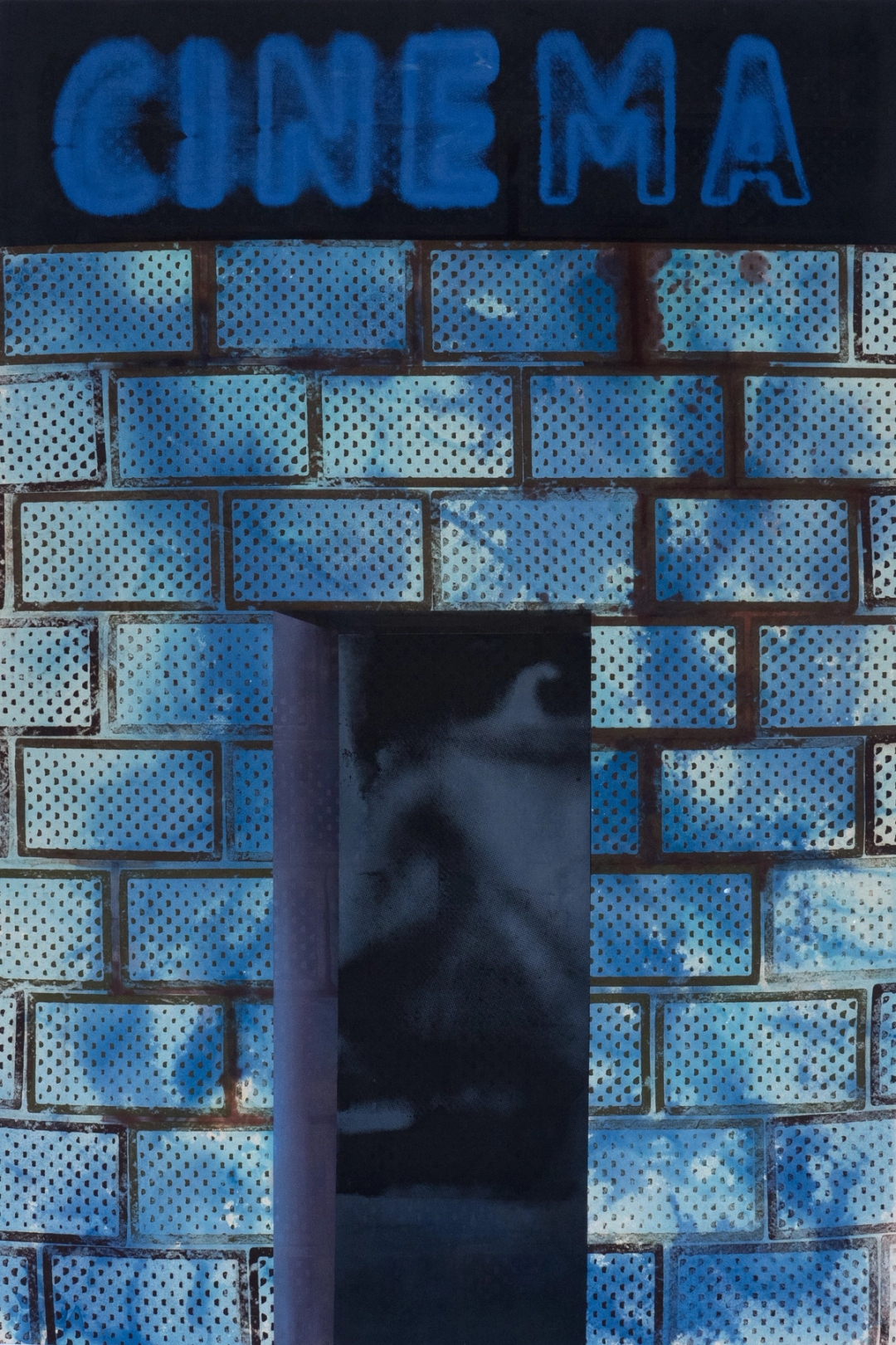

Jay Heikes, Phantom of the Underground, 2023

Oil on stained canvas. 112 x 75 in.

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (from the series "My Mother’s Flowers"), 2016

Archival pigment print, Edition of 3 + 1AP. 20 x 16 in.

Alexa Horochowski, Naturaleza Muerta Con Una Liebre (Still Life With A Hare), 2024

Gold-plated bronze, bronze, pewter, lead, wood

Kim Benson. Tileset, 2024. Oil and enamel on shellacked linen over panel. 18 x 24 x 1¾ in.

Justine Di Fiore, Undergrowth, 2024

Oil on Canvas (Diptych). 30 x 53 1/2 in.

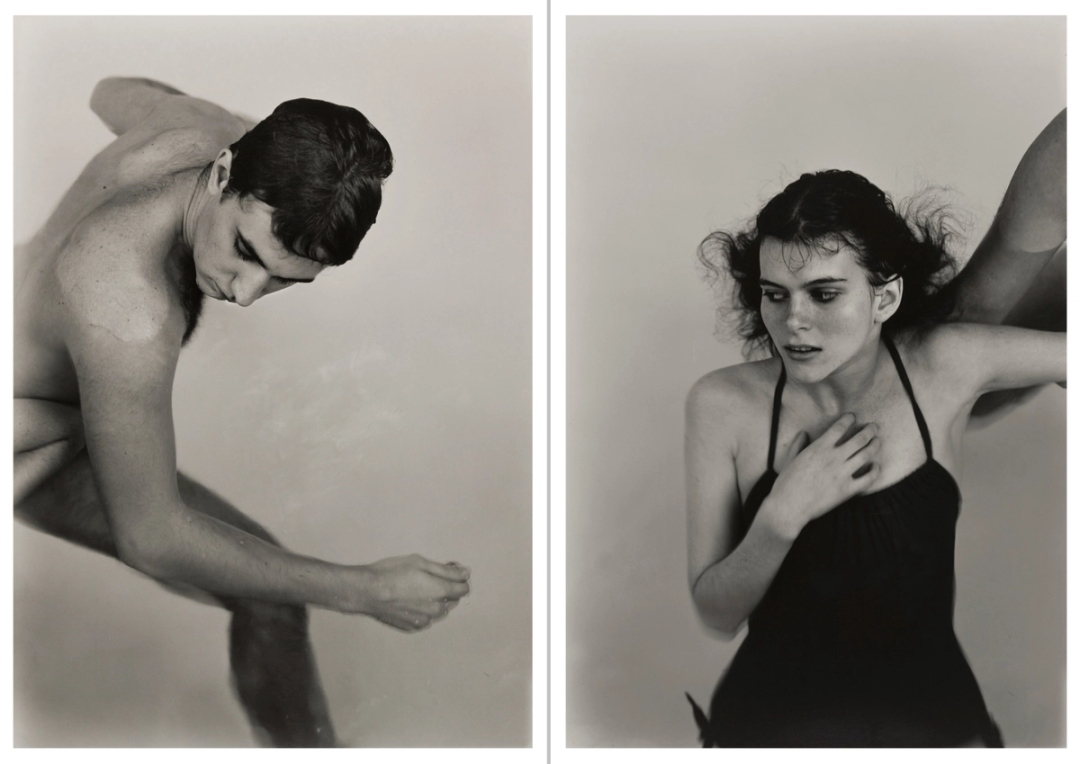

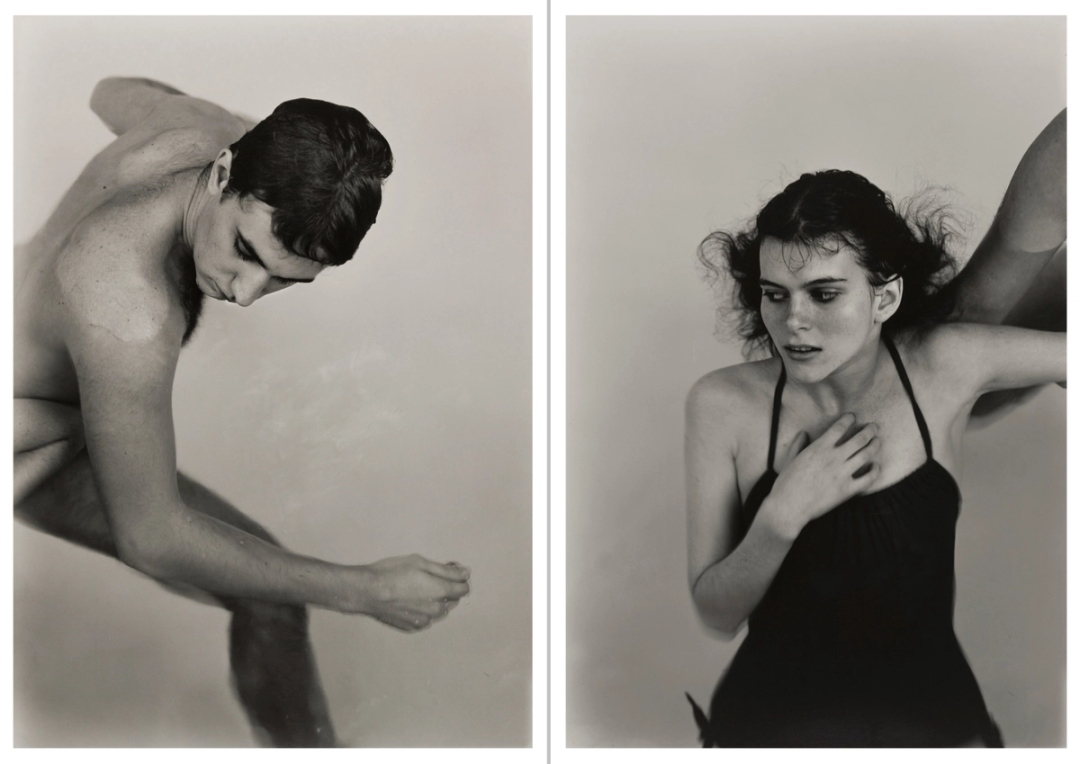

JoAnn Verburg, After Giotto, 1983

Two gelatin silver prints, Diptych, Ed. of 5. 34⅝ x 241⁄8 in. ea.

JoAnn Verburg, Four Times Three, 2007

Chromogenic Print on Endura, ed. 8 of 10. 39⅜ x 110 in.

Moyra Davey, Forks & Spoons, 2024

HD Video with sounds, 26:33 mins

Justine Di Fiore, Undergrowth, 2024. Oil on Canvas (Diptych). 30 x 53½ in.

David Goldes. Under the Sheltering Sky, 2024. Graphite, molding paste, black gesso on paper. 27 x 22 in.

Ruben Nusz, After Morandi, 2019-2024

Distemper on linen. 8 x 10 in.

Ruben Nusz, After Morandi, 2019-2024

Distemper on linen. 8 x 10 in.

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (from the series My Mother’s Flowers), 2016

Archival pigment print, Edition of 3 + 1AP. 40 x 32 in.

Ruben Nusz, After Morandi, 2019-2024

Distemper on linen. 8 x 10 in.

Jay Heikes, Phantom of the Underground, 2023

Oil on stained canvas. 112 x 75 in.

Pao Houa Her, Untitled (from the series "My Mother’s Flowers"), 2016

Archival pigment print, Edition of 3 + 1AP. 20 x 16 in.

Alexa Horochowski, Naturaleza Muerta Con Una Liebre (Still Life With A Hare), 2024

Gold-plated bronze, bronze, pewter, lead, wood

Kim Benson. Tileset, 2024. Oil and enamel on shellacked linen over panel. 18 x 24 x 1¾ in.

Justine Di Fiore, Undergrowth, 2024

Oil on Canvas (Diptych). 30 x 53 1/2 in.

JoAnn Verburg, After Giotto, 1983

Two gelatin silver prints, Diptych, Ed. of 5. 34⅝ x 241⁄8 in. ea.

JoAnn Verburg, Four Times Three, 2007

Chromogenic Print on Endura, ed. 8 of 10. 39⅜ x 110 in.

Moyra Davey, Forks & Spoons, 2024

HD Video with sounds, 26:33 mins

In his short story, Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote (1939), Jorge Luis Borges discusses the reproduction of a seminal text far removed from the historical and social context of the original. Menard, the titular character, channels his own experience to precisely rewrite chapters of Cervantes’ Don Quixote without directly copying the text. Of course, the Quixote as written by an early twentieth century Frenchmen carries far different meanings and connotations than the Quixote as written by a 16th century Spaniard, and to Borges, Menard’s conceptual project invites a new manner of reading:

"Menard has (perhaps unwittingly) enriched the slow and rudimentary art of reading by means of a new technique – the technique of deliberate anachronism and fallacious attribution. This technique fills the calmest books with adventure. Attributing Imitatio Christi to Louis Ferdinand Céline or James Joyce – is that not sufficient renovation of those faint spiritual admonitions?"

Discursive questions surrounding authorship and context lie at the root of Menard; the same have been contemplated throughout the history of art. As in literature, time is all important: contemporary art exists in a Heraclitean swirl of discussion and context that is constantly in flux.

"Every artist works relentlessly to shed the irresistible references of their idols, some more than others, but those influences never truly go away. They are ghosts that forever haunt the artist and without constant exorcisms they become too seductive to ignore, usually grabbing hold every once-in-a-while for a Faustian pas de deux - a bargain that is a simple one; material pleasures over spiritual ones, resulting in a derivative, didactic conduit instead of an original, abstract belief system. But maybe originality is overrated or a flat out myth..." (Jay Heikes)

With references to Giotto, Michelangelo, Morandi, and Paul Thek, among others, the featured artists in Dreamsong’s summer group show explore what it means to appropriate another artist’s work, either directly or slyly, wholesale or in part, and how distinctions between homage, facsimile, commentary, subversion, and criticism bend and shift, allowing the past to be ceaselessly reread in the present.

Artist(s)

Kim Benson, Moyra Davey, Justine Di Fiore, David Goldes, Jay Heikes, Pao Houa Her, Alexa Horochowski, Ruben Nusz, JoAnn VerburgPress

Critics' Pick by Andy Graydon

Artforum 7/25/2024

Critics’ picks: The 15 best things to do and see in the Twin Cities this week by Alicia Eler

Star Tribune 7/8/2024

Dreamsong: Pas de Deux exhibit draw on artistic heroes for inspiration by Sheila Regan

Minnpost 7/2/2024